So long as you don't feel silly, it's the others who are: ‘Bon Voyage’ by Damon Tong

Interview by Ho Sin Tung, 19 January 2022

Translation: Mary Lee

Original text in Chinese: https://p-articles.com/heteroglossia/2711.html

Developed from the previous ‘World Peace’ series and taking the Aeroplane Chess as its central motif, the exhibition continues to explore the theme of childhood games as a reflection of the current social situation.

When it comes to Damon Tong and his works, a bunch of keywords suggest themselves: ‘sticker’, ‘Made in Hong Kong/China’, ‘Pop’, ‘Rental United’, ‘gasbag’, i.e. a person who talks too much, though not at all derogatory. After all, we are all accustomed to the intensive dialogues of such gasbag films by the likes of Éric Rohmer, Woody Allen and Richard Linklater, which seems to have become one of those widely accepted mainstream styles ever since Jesse Eisenberg and Tom Holland. Instead, I would like to focus on another keyword associated with Damon Tong: ‘paradox’.

First I must explain, when I say ‘paradox’, I am not referring to a logical confusion or discrepancy as a result of dissimulation, but that in him there is often this sense of contradiction that raises one’s eyebrows.

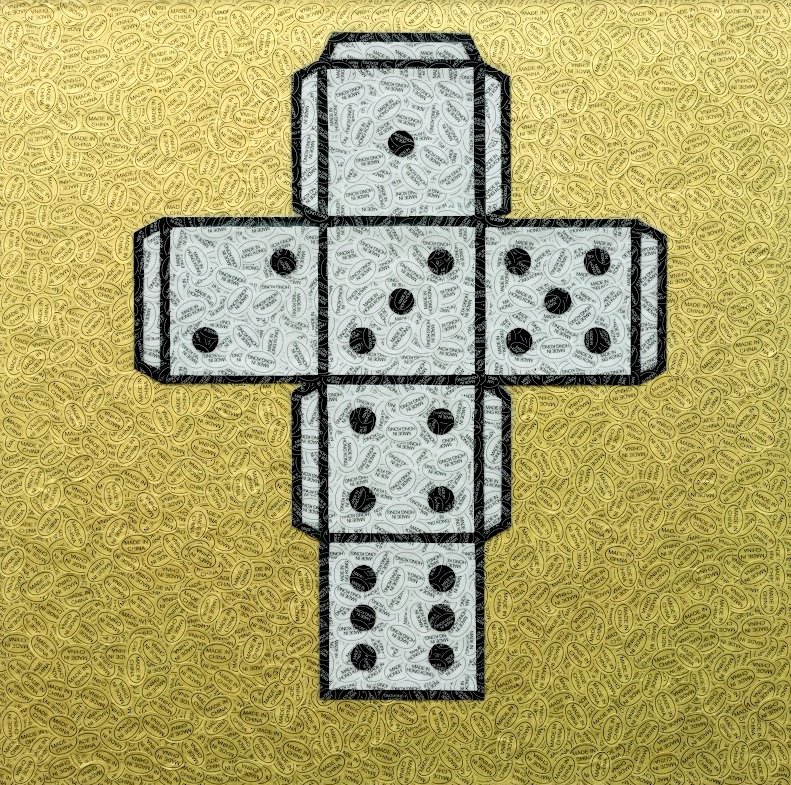

Always having to express his opinion on almost everything, he often digresses. Consequently, a lot of what he truly means to say remains unsaid. For surely we often notice the outpouring of the speaker, without being aware of the words he or she swallows, how many there are, wherefore they have gone. For example, in his old work maan ngok jam wai sau, the five big characters are split into five panels and hung up high. It is a minimal manifestation, but when you mention it, he would babble on, about Naamyam, Sun Ma Sze Tsang, the evolution of lust, excess and avarice…… an immense amount of information and enthusiasm which he chooses not to display. The fragmentary and densely arranged stickers may point to myriad references, yet at the same time do not seem to convey much at all, even when they constitute the body of another vocabulary. Hence I always have a feeling that the repressiveness in his works has to do with all those things that go unsaid.

maan ngok jam wai sau is nevertheless more eloquent than his other phrases. His usual choices tend to be more vernacular, such as ‘sorry’ (all in lowercase), ‘cold drink + $2’, ‘What are you doing’, etc. Even the title of this exhibition ‘Bon Voyage’ is no exception, being empty words like ‘safe trip~’ or ‘enjoy!’ that one says without meaning anything. Developed from the previous ‘World Peace’ series and taking the Aeroplane Chess as its central motif, the exhibition continues to explore the theme of childhood games as a reflection of the current social situation. In the past two years, the pandemic has made flying a luxury and sometimes an impossibility, while many emigrate, making it a sort of final farewell. Blessing or sarcasm, ‘Bon Voyage’ means that everyone of us must be reminded of someone who has left, and all the inexplicable feelings that entail.

Truth be told, when we played World Peace as children, the game would soon turn into a fantastical arms race where the newest fighter jets, UFOs and all kinds of flying beasts were born on paper, as we fought each other to the death. The game in Damon Tong’s works is however very neat and regulated, yet probably closer to the spirit of the game. This is elucidated in ‘Ivan and Abdul’, chapter 6 of The Grasshopper: Games, Life and Utopia, Bernard Suits’s book on the philosophy of games and gaming: ‘A number of breathtaking refinements were added to most of the conventional games. Thus to golf was added, among other things, the use of self-propelling radar-controlled golf balls, and to chess the use of hallucinogenic drugs as an offensive weapon… The instant of setting out the pieces for a game would be the signal for us to start a battle whose weapons had nothing whatever to do with chess, since the only moves either of us will accept are moves that really coerce, either by force or by deceit. For, since we will not abide by the rules of the game, the winner can be only he who has gained final mastery of the situation. And of course, it’s not only that we can no longer play chess. For the same reason, we can no longer play any game, for games require that we impose artificial restraints upon ourselves in seeking victory, and we refuse to do that.’ Indeed, one important essence of games has nothing to do with gratification, but restraint. The artist can of course appropriate the classic games, adding or taking away certain rules or elements, rendering them completely unplayable or totally ineffective, as in the UNO series Damon Tong shows me, in which only the ‘Reverse’ card remains of the entire deck of cards. If we play it in truth, it will become a real eternal hell of a game.

There is a reason why he has so faithfully reproduced the World Peace and Aeroplane Chess games. Imbued with war metaphors, the games, despite the excitement, are still kind of silly, unless practised through playing. Aeroplane Chess belongs to the category of cross and circle race game. According to R. C. Bell’s Board and Table Games from Many Civilizations, games with similar structures have appeared in different eras and countries, including the Korean ‘Nyout’ from 1122 BC, the ‘Patolli’ introduced from Spain to the Aztec Empire in 1552, the Indian ‘Pachisi’, finally and closest to today’s Aeroplane Chess is ‘Ludo’, evolved from ‘Pachisi’ in 1869 and patented in the United Kingdom. Baidu of the great Fatherland states: ‘This is necessarily an original creation by the Chinese, produced by a Chinese toy company to commemorate the outstanding achievements of the Flying Tigers during World War II, and is a variant of the Pachisi.’ The fighter jets have since disappeared, replaced by commercial aircrafts. The imagery is of the planes criss-crossing along several trajectories in the air, while in reality they are just dragging along by the luck of the dice. Occasional attacks may happen, where opponent planes are returned to the hangar, but on the whole, compared to the complexity of today’s board games, Aeroplane Chess cannot be said to be very interesting. Yet this is exactly why Damon Tong finds it wonderful, where coming and going, gathering and separating, are all futile.

He also emphasises how the four-coloured hangars are ‘really ugly’: ‘That Chinese primary colour printing, the primitive red, saturated yellow… you can always tell the Chinese colour scheme.’ Yet he never tampers with it. Complaining, he reproduces the colours as they are religiously. The artist’s aesthetic decision is based on reality instead of beauty. Responding to the four colours, in another work in the exhibition, Chess Board 1, the Aeroplane Chess is converted into black and white and arranged into a chess formation. No more Queens, Kings, Bishops; just dispensable, cookie-cutter Pawns. He says it reminds him of the art world. An artist of the floating world, where you do not make the rules. Advance or retreat, you will always remain a Pawn on the chessboard that can be replaced at will. This is another paradox of Damon Tong. While he often grumbles about the art world and the art market, still he has been creating tirelessly years since leaving art school, putting much consideration into his works, as if the game is worth the while after all. Talking about the small Aeroplane Chess roundels, he says they meet the gallery’s sales demand for works in different sizes, and isn’t that cool? That is obviously a commercial consideration, and yet his smile is so innocent.

Has he ever thought of a change after so many years making sticker paintings? He thinks he can go on forever. Like many artists who use repetition as a creative method, he refers to ‘meditation’. Do the stickers give you room to contemplate different questions, or do they leave your mind completely empty? He cannot tell, except that he is oblivious of time passing, and only wants to keep sticking. I am reminded of Hungarian psychologist Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi’s psychological concept of ‘flow’: ‘What is flow? It is a special mental state when you are extremely focused and fully immersed into something, your efficiency and creativity is increased, you forget about time, about hunger, even all irrelevant bodily signals.’ And this is the very state Damon Tong finds himself in. Csikszentmihalyi indicates five conditions to achieve ‘flow’: ‘One, love what you do; two, possession of certain skills and the ability to master what you do; three, it has to be challenging but not too challenging, just slightly more difficult (by 10%) than your current ability; four, occasional feedback and reward; five, a clear goal and a basic idea of the procedure.’ One activity that best embodies these five conditions is gaming. I know that Damon Tong spends a lot of time playing computer games. I think perhaps when the stickers get too repetitive he would play something really extravagant to unwind, but he tells me that his favourite game is ‘Builderment’. On the App Store the description reads: ‘Builderment is a factory building game at heart. It’s all about crafting and automation. You start by harvesting resources and crafting items in factories. Use those crafted items to research new technology and recipes to craft ever more complex items.’ Repeated mechanised parts and pipelines neatly fill the screen, and I have to say if there is any game he would immerse in, this is the one.

While his ‘Made in China’ and ‘Made in Hong Kong’ stickers come from his childhood in the 1970s and 1980s, when he was introduced to these labels through his family in the textile business, I cannot but be reminded of the sticker on the foil wrapping of Ferrero Rocher, a vulgar gift that is a huge excess in itself, the sticker even more superfluous, some useless thing to be discarded right from the start, even when it is there to state its purpose. And to be honest, I have always been afraid of stickers. For it is such a stubborn abjection, carelessly left behind, smeared with dust and dirt, refusing to go away. Julia Kristeva states in Powers of Horror: An Essay on Abjection: ‘In the first place, filth is not a quality in itself, but it applies only to what relates to a boundary and, more particularly, represents the object jettisoned out of that boundary, its other side, a margin.’ Even so, I participated in the inaugural event of his Aeroplane Chess, and touched his stickers without fear, for no other reason than that his stickers were carefully arranged, and a matte glue gesso was applied to the surface to make them secure and smooth. While his works seem to be conceptually driven, in our conversation he mostly talks about material, colour, texture… in the language of painting. This is another raised eyebrow. After contemplating all these topics, I think none of that matters, since at the end of the day, his biggest motivation to create is really just the ‘joy of painting’.

Damon Tong has said, ‘I don’t think your article will be very juicy.’ Is that so? Still there is something I have to say. I asked him, ‘Are you a herbivore man, Damon?’ He said, ‘No, I eat meat. It’s just that instead of the buffet I desire a canteen meal.’ I think this, more than all the nonsense above, sums up his creation perfectly.